My introduction to this style of oil painting was under the instruction of master painter Snowden Hodges, at the University of Hawaii, Windward. Snowden is now professor emeritus and continues to paint and spin his magic exhibiting his beautiful work throughout the islands of Hawaii. Snowden’s work can be seen on his website:

http://www.snowdenhodges.com/Contemporary_Realism/Snowden_Hodges.html

This style of painting uses the technique of the Old Master painters: Rubens; Rembrandt; Veronese; Hals, to name a few. The raw canvas is stretched and sized with rabbit skin glue. This is the followed by several coats of tinted (pale grey) “Gesso”. This is a mixture of glue, water, and whiting used for priming a painting surface to protect the fabric from deterioration from the oil. It also creates a smooth surface to begin the drawing.

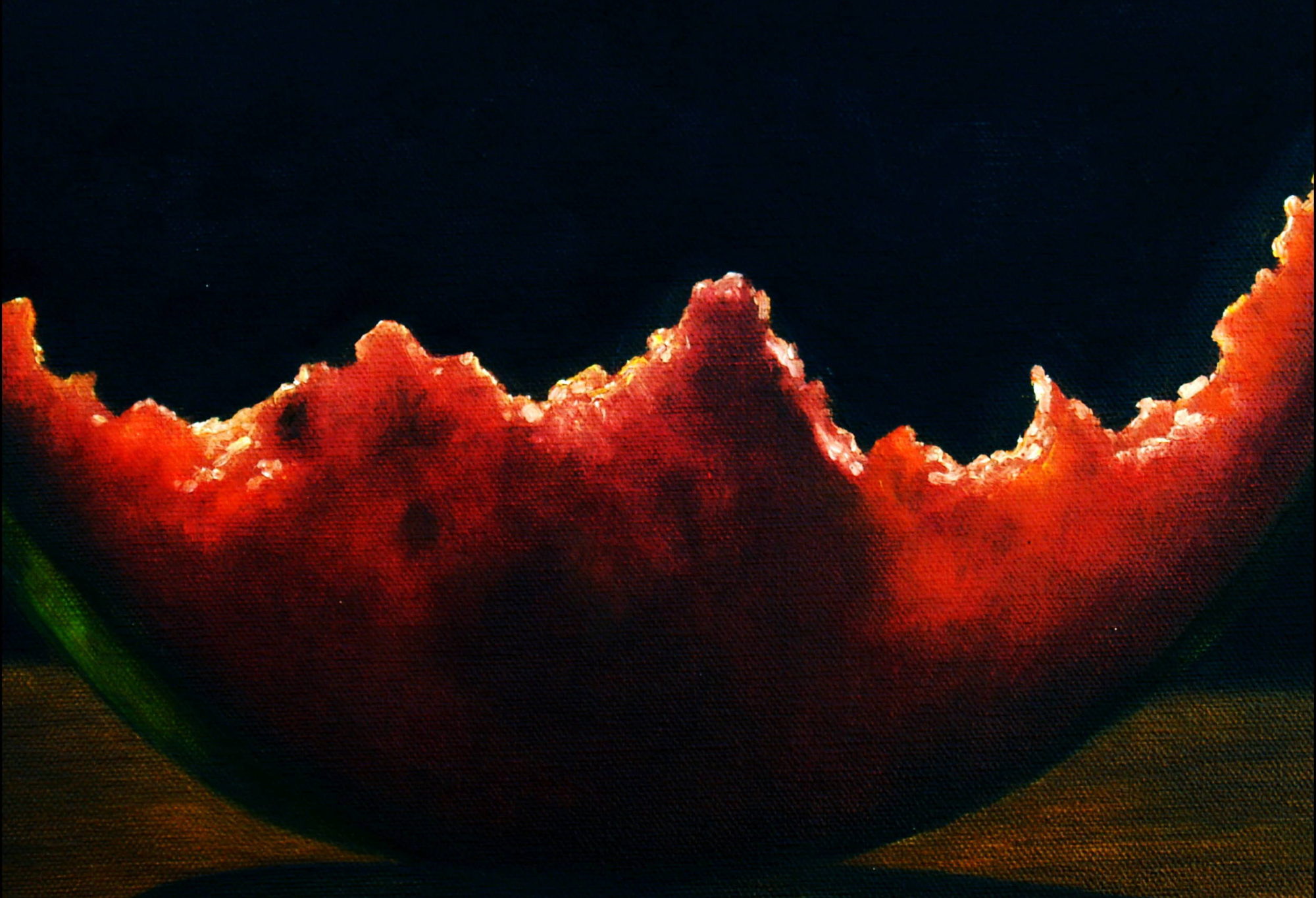

The drawing is rendered in burnt umber paint with a fine brush, not pencil. This is called the underpainting. Another form of underpainting is “Grisaille”, a painting which is rendered in black and white. When the “drawing” is complete it should resemble a sepia picture. All the lights and shadows are established in various tones of umber. We paint using a “Medium” that is a mixture fo litharge of lead, cold-pressed linseed oil and beeswax. This mixture is cooked and cooled in a jar and has a soft buttery consistency.

The Medium we use is that created by Jacque Maroger, a noted restorer and chief conservator of the laboratory at the Louvre in Paris, France. It is said to be similar to the original medium used by the Old Masters. In using this technique and medium, you get the vibrancy and clarity of color and depth. These paintings will retain their original quality and luster for centuries unlike many contemporary methods today.

When the underpainting is thoroughly dry, light glazes of color are applied. In certain areas that we want to highlight we use a heavier application of opaque paint that usually shows the marks of the brushstroke.

Once the painting has dried completely (recommended 3 – 6 months) we apply two light coats of varnish.

Below are two examples of the process. You will see in the first rendering of the first image that the bottom half is a sketchy light drawing. Then, working upwards, I begin to fine tune by deepening the layers of umber paint to create the dramatic lights and shadows (Chiaroscuro) of the painting. Every light and shadow must be established in the underpainting prior to the application color.

In the other image below, Palazzo D’Avanzati, you will see the completed underpainting.

The Crowded Room:

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Palazzo D’Avanzati:

Firenze, Italy

The Maroger Medium:

“When Jacques Maroger arrived in Baltimore to join the faculty of the Maryland Institute of Art, he was 56 years old and an accomplished painter, teacher and restorer. He had made the difficult decision to leave Paris and his positions as technical director of the Laboratory of the Louvre in Paris, where he also taught in the museum school, and the presidency of the Restorers of Art in France. He settled first in New York City, where he accepted a professorship at the Parsons School of Design.

Maroger always said that his familiarity with the old masters’ techniques was what made him a good teacher and restorer. This familiarity came from his training as a painter. Maroger studied first with the French portrait painter Jacques Emile Blanche, who later sent Maroger to study with his friend and fellow countryman, artist Louis Anquetin (1861 – 1932). Anquetin had himself been a student of Van Gogh and a friend of Toulouse-Lautrec, Degas and Renoir. After a brief flirtation with Impressionism, Anquetin returned to the study of the old masters, Rubens, Hals and Rembrandt, trying to rediscover their lost painting techniques. Following Anquetin’s guidance, Maroger copied paintings of the old masters and studied anatomy in a dissection class of a medical school as he took up and continued his teacher’s research into the colors of the old masters’ pigments and the brightness, transparency and permanence of their canvases. Maroger was to continue this research throughout his life.

In 1929,while at the Louvre, Maroger was credited with discovering the first oil painting medium of the 15th-century artist Jan Van Eyck. This initial discovery was published by the British Academy of Science in 1931, arousing the interest of the critic Roger Fry, who invited Maroger to give a painting demonstration. A number of English artists, among them Augustus John, then became enthusiastic users of this new medium. In 1937, when Raoul Dufy was commissioned to paint a 36 x 220 ft. painting of L’Histoire de l’Electricite for the Paris World Fair, he used the Maroger medium, choosing his friend Jacques Maroger as his technical adviser. Later that year, Maroger was awarded the Legion of Honor for his contribution.

Maroger was best known for his rediscovery of the mediums of Jan Van Eyck and other Flemish and Italian Renaissance painters long before his research was published in 1948 in his book The Secret Formulas and Techniques of the Masters. But his strong feelings about the proper training of young artists was also becoming equally well-known in Baltimore. Maroger emphasized the technical foundations of painting in his courses. Just as he had been urged to study anatomy and return to the museums to copy the work of the old masters, so he required that course of study for his new students at the Institute. Maroger also insisted that his students prepare their own medium by combining and cooking oils, lead oxide and other substances according to formula. Maroger further insisted that his students grind pure colors for mixing with the medium. Only with these materials could they begin to reproduce the colors and luminosity of the old masters.

As Maroger began giving his Institute students an intensive training in anatomy, drawing, sculpture, portraiture and still life painting, combined with instruction in how to grind pigments, hand-press linseed oil and make mediums, he also began dreaming about the development of an American school of painting, grounded in that knowledge. The first to join Maroger as a postgraduate student and as an assistant was Ann Didusch Schuler, who remained his teaching assistant throughout his 19-year tenure at the Maryland Institute. In 1946, Maroger’s student group included Frank Redelius, Earl Hofmann, Evan Keehn, Joseph Sheppard, Elizabeth Byrd Mitchell, Thomas Rowe, John Bannon and Guy Fairlamb, often referred to as his disciples. During these years, the 1940s and 1950s, many established artists came to Baltimore to learn about the Maroger medium directly from Maroger. One such artist was Reginald Marsh, who came down from New York every summer for more than 10 years until his death in 1954. Marsh had a very strong influence on these young artists and exhibited enthusiastically with them and Ann Schuler and Maroger at the Grand Central Gallery in New York and at the Mt. Vernon Club in Baltimore.

…By 1961, those early students of Maroger were making headlines. …Two thousand people attended the Six Realists Gallery opening. The headlines the next day read, “A triumph in every way.” The News American,critic R.P. Harris wrote a strong review, stating, “Whether this group will form the nucleus of a recognized school dedicated to bucking the non-objective craze remains to be seen. As of now, they are a credit to their patron, St. Maroger.” In addition to the founding members, other artists who formed the group of Six Realists were Melvin Miller, Guy Fairlamb, Ronald Reillo and David Walsh. Often paintings by the Six Realists were juried into the annual exhibits at the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio. Most notable was the inclusion of work by Sheppard, Rowe and Miller in the 1962 Annual, along with work of Ben Shahn and Edward Hopper. In 1963, the Butler organized an exhibition of 40 paintings by the Six Realists, which traveled to the Vanderlitz Gallery in Provincetown, Massachusetts and to Baltimore. The Six Realists were putting Baltimore on the map and gaining new confidence for the pursuit of their art.

…All the artists represented in this exhibition have practiced Maroger’s method and used his mediums and, with few exceptions, all teach or have taught as he did. They have continued in the path Maroger described for his students in a 1956 letter to Siegfried Hahn in New Mexico, when he said, “they are now the marvelous apostles of true painting – and each of them teaches…which is spreading the good word.”

-Essays by Cindy Kelly, Curator of Evergreen House